|

|

> archived articles

> write for core! be famous!

From the Trenches: Marketing a Design Firm

Part 2: Making the Leap

by Joseph Dennis Kelly II

|

|

Dropping the safety net of a full-time job and launching a solo career can be an alluring yet daunting decision for anyone. For Jeff Miller, who gave up his role as VP of Design at a prestigious Manhattan design firm to pursue this dream, it was almost inevitable. The desire for recognition of his own work, his own decisions and sensibilities was something ingrained in his spirit from the earliest days of his design education. After paying his dues, through years of consulting work and previous design endeavors, his career as an independent designer is beginning to take off.

|

|

The Call

While Miller was an undergrad industrial design student at Pittsburgh’s Carnegie Mellon University in the late-1980s, he often dreamed of a solo career making brilliant objects that leading manufacturers would mass-produce and distribute around the world.  After graduation, however, looking for direction, experience and a regular paycheck, he turned to the world of design consulting, He was soon hired as the first full-time employee of a start-up design consultancy in an office so cramped he literally rubbed elbows with the firm’s principal, Eric Chan. Working closely with a talented designer like Chan has its benefits, and over the years Miller helped build ECCO into what is today a well-respected 15-member team of top-notch designers. After graduation, however, looking for direction, experience and a regular paycheck, he turned to the world of design consulting, He was soon hired as the first full-time employee of a start-up design consultancy in an office so cramped he literally rubbed elbows with the firm’s principal, Eric Chan. Working closely with a talented designer like Chan has its benefits, and over the years Miller helped build ECCO into what is today a well-respected 15-member team of top-notch designers.

By 1995 Miller had reached an enviable level of success; five years of experience with one of the nation’s top design firms, dozens of successful products in production and living and working in Manhattan. Yet even during those first busy years, Miller still yearned to make his mark as a solo designer. He wanted to break free of the design consulting routine, he wanted to test market his own concepts and creations. He hooked-up with Carnegie Mellon design chum Sandy Greene, and together they co-founded Miller Greene, a furniture design and manufacturing firm that gave Miller a first-rate education about the business of design.

|

|

The Quest

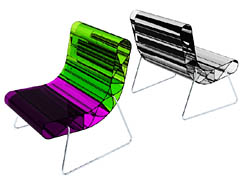

Instead of focusing their attention on creating and producing conventional marketing and publicity materials to kick-off their new venture, Miller and Greene developed and prototyped an inaugural collection, which included a modular seating unit by Miller, that they unveiled at ICFF 1996. Despite the positive feedback they received, their showing failed to deliver on their hopes of generating several orders and reaping the financial rewards of their endeavor. Their exhibition was, in fact, a financial disappointment. In analyzing the reasons why this effort failed to match their expectations, Miller realized that “people show up at ICFF to see who you are. When you’re around for two years, ICFF visitors will place orders, but they don’t bank on someone who just shows up.” In the months that followed, Miller and Greene tried to keep their firm going by pursuing consulting work. By 1997, when future projects failed to materialize, Miller Green dissolved.

“The venture was a big lesson in how design and business really need to go hand-in-hand to make a successful venture,” explains Miller, who cites their not having a clearly defined business strategy as a factor in of the venture’s failure. “It’s not enough to put great ideas in front of manufacturers because there are so many great ideas in front of so many people now. Market success is really 10% about having great design and 90% business acumen. What I learned from the Miller Greene experience was that to make an impression is a better investment in one’s own time and resources. The best thing for new firms is to put the name and objects out there and just let people see what they’re trying to express, without—in my case—muddying it with trying to start a business of supplying furniture at the same time.” What most amazed Miller in the months that followed ICFF 1996 was the feedback he received from friends and peers who had only heard about the exhibition or had seen pictures of the modular seating and table pieces he designed in a magazine. “People started to respect something about me and my design for the sake of having done that,” he says. The exhibition showed him that just showing the work can be a highly effective method for marketing and publicizing design, for connecting objects and communicating design concepts with other people, and for getting the word out about new ideas. Much more so than a conventional media kit showing photos of objects, where the impact of the object cannot be fully understood, comprehended or experienced in a non-physical format and non-tactile context.

|

|

The Struggle

Despite his disappointment, Miller learned that successful firms think about longevity and don’t allow themselves to get lost in the micro-issues of day-to-day operations. He learned that catchy ploys and outlandish displays pale in comparison to building market credibility and industry recognition through continuous presence at events like ICFF. He also learned that he did not want to spend his time managing a manufacturing business, that he wanted to design objects that others would manufacture for him. He stored this knowledge in his mind, knowing he would call upon it one day.

The Miller Greene experience took him to a new level as a designer. A self-proclaimed perfectionist, Miller was delighted to have broken free of his inhibitions, if only for a few months, and to have lived the dream of a solo design career, an aspiration he had since he first came upon the field of industrial design, when he found, in the library of his West Chester (NY) high school, a book on Raymond Loewy. After reflecting on the Miller Greene venture and reconnecting to the passion he felt when he first read about Loewy, he knew he was on his path, a fact that was affirmed when his Miller Greene modular seating unit won an I.D. Magazine 1997 design award. The Miller Greene experience took him to a new level as a designer. A self-proclaimed perfectionist, Miller was delighted to have broken free of his inhibitions, if only for a few months, and to have lived the dream of a solo design career, an aspiration he had since he first came upon the field of industrial design, when he found, in the library of his West Chester (NY) high school, a book on Raymond Loewy. After reflecting on the Miller Greene venture and reconnecting to the passion he felt when he first read about Loewy, he knew he was on his path, a fact that was affirmed when his Miller Greene modular seating unit won an I.D. Magazine 1997 design award.

By late 2001, after having sufficiently recovered from the financial and psychological wounds incurred from Miller Greene, Miller was ready to try the solo designer track again. Working on his own, he decided to act as a client to himself. He developed a project brief, defined his ideas, refined his designs, created a project budget, conducted a manufacturing feasibility study, prototyped the objects and found an empty SoHo storefront where he exhibited his work during ICFF 2002 in a solo exhibition entitled “Critical of Mass.” His approach to this exhibition was simple: “Here’s me and here’s some of the things I do.” Once the public started coming in, he felt their excitement. The show became his media kit. Attendance was phenomenal. Visitor feedback—which served as his benchmark for analyzing his effort—far exceeded his expectations.

|

|

The Breakthrough

As word got out about his exhibition, magazine editors and manufacturers came to him. One Japanese manufacturer approached Miller about including some of the featured objects in an upcoming collection. Though this never materialized, Miller witnessed the evolution of his name—almost overnight—from design consultant to innovative furniture designer. And when the show closed, he was left wanting more. He knew he found something meaningful for himself that was valued by other people. Friends and associates who missed the show congratulated him, sometimes—like his Miller Green venture—months afterward, after hearing from others about his storefront presentation. The success of the show inspired him to make the leap. On January 1, 2003, Miller officially left his full-time position at ECCO—though he continues a relationship as a part-time consultant on specific projects—and opened the doors of Jeff Miller Design (www.jeffmillerdesign.com).

In the thirteen months since going solo he has completed five projects for three clients and closely observed the public response to his objects. He purposefully did not create a business plan or mission statement for his new venture because, he believed, such constraints would deter a more organic evolution of his firm and would impose an identity that he is not ready to accept. An expert in developing products for targeted markets, Miller believes in using consumer response to help guide his process of defining his firm and codifying its strategy. A solo designer with limited resources, his intent is to prototype several of his ideas into objects that he can present to the public. He also believes that developing prototypes is a key for selling manufacturers on an object. Before including items in a collection, manufacturers need to know that the designs can be produced as affordable consumer products. Renderings, he adds, are pie-in-the-sky stuff.

During ICFF 2003, he showed his work in yet another storefront-style exhibition, this time in a group exhibition at the Chelsea Hotel organized by the Downtown group and entitled “Downtown at the Chelsea Hotel.” And while this show again generated much enthusiasm for his work, it was his selection to Surface Magazine’s 2003 T.A.G. Team and the inclusion of his work in Surface’s 2003 Salone del Mobile and ICFF installations—as well as Surface’s special ICFF 2003 off-site show at a Chelsea museum—that really catapulted Miller onto the industry’s radar screen as an important emerging solo designer. Riley Johndonnell, brand creative director for Surface Magazine, writes via email that he selected Miller for Surface’s 2003 T.A.G. Team because Miller “seems less concerned with embedding his ego into the design object,” adding that in Miller’s work “function, innovation and beauty come first…It’s very pure design where aesthetic is influenced by the function. His signature does come through in the design, but not in a forced way. His pieces seem to speak of a process: in each piece you can see solutions to problems, you can see the designer’s thought process.” These exhibitions of Miller’s objects caught the eye of Joey Tessalona, design director at Clinton’s Felissimo Design House. Tessalona, who calls Miller a "great upcoming designer," selected Miller’s aluminum bed for inclusion in Felissimo’s recent “Life Symphony” exhibition. During ICFF 2003, he showed his work in yet another storefront-style exhibition, this time in a group exhibition at the Chelsea Hotel organized by the Downtown group and entitled “Downtown at the Chelsea Hotel.” And while this show again generated much enthusiasm for his work, it was his selection to Surface Magazine’s 2003 T.A.G. Team and the inclusion of his work in Surface’s 2003 Salone del Mobile and ICFF installations—as well as Surface’s special ICFF 2003 off-site show at a Chelsea museum—that really catapulted Miller onto the industry’s radar screen as an important emerging solo designer. Riley Johndonnell, brand creative director for Surface Magazine, writes via email that he selected Miller for Surface’s 2003 T.A.G. Team because Miller “seems less concerned with embedding his ego into the design object,” adding that in Miller’s work “function, innovation and beauty come first…It’s very pure design where aesthetic is influenced by the function. His signature does come through in the design, but not in a forced way. His pieces seem to speak of a process: in each piece you can see solutions to problems, you can see the designer’s thought process.” These exhibitions of Miller’s objects caught the eye of Joey Tessalona, design director at Clinton’s Felissimo Design House. Tessalona, who calls Miller a "great upcoming designer," selected Miller’s aluminum bed for inclusion in Felissimo’s recent “Life Symphony” exhibition.

|

The Return

Eric Chan, Miller’s mentor and former employer, says that the most important thing any new venture can do is to differentiate itself in innovative ways that ensure the industry and the market understand what the firm stands for. “There is no one formula to running a design business, just as there is no one formula for design,” says Chan. “Every part of running a business requires different approaches each time because the reasons change. Find a new reason to guide the process, otherwise what was created and used before will be repeated continuously.” He goes on to note that design and business theory only work when used in practice, not when used to build brand. “What’s most important is output,” he says. “People today are overanalyzing and not doing enough. A fair amount of marketing and public relations is necessary to grow, but one can overkill by doing too much. Today, one doesn’t need to exert a lot of effort to build recognition. In Italy, the whole industry has very little to do with production, but a lot of story-building. Building a story is not wrong, but I don’t think one can depend on it to launch a career….Keep doing good work. Be focused. Get the work out. Then try to react to the market. There are many mediocre designers and we don’t need another one. Know that you are good. Know what you stand for as a designer.”

Johndonnell, known for favoring designers with an innovative perspective of—and distinctive approach to—design, agrees with Chan, writing that “young designers today have been swayed by the new sense of celebrity that has wrapped many ‘big’ designers. Young designers seem preoccupied with creating logos and marketing materials, and not enough with the prioritization of their product. I can’t tell you how often I get a great presentation of marketing materials for a crap product—a 3D rendering of something that is essentially slick shiny crap. Designers need to have a business strategy. Knocking on the door of manufacturers doesn’t count. That’s simply one element of a plan. Designers these days seem to carry themselves like a garage band, carrying demos, playing a gig here and there, then hoping to ‘be discovered.’ Rarely does it work this way. Designers need to know how to sell ideas, themselves and product. That’s the business. Know the potential of how you and your products can affect the world around you…a good piece of design and a good designer emote something to others.” He suggests that designers looking to get media attention pitch stories rather than products to editors. “Everyone like exclusives—pitch a different angle to each editor you approach.” Johndonnell, known for favoring designers with an innovative perspective of—and distinctive approach to—design, agrees with Chan, writing that “young designers today have been swayed by the new sense of celebrity that has wrapped many ‘big’ designers. Young designers seem preoccupied with creating logos and marketing materials, and not enough with the prioritization of their product. I can’t tell you how often I get a great presentation of marketing materials for a crap product—a 3D rendering of something that is essentially slick shiny crap. Designers need to have a business strategy. Knocking on the door of manufacturers doesn’t count. That’s simply one element of a plan. Designers these days seem to carry themselves like a garage band, carrying demos, playing a gig here and there, then hoping to ‘be discovered.’ Rarely does it work this way. Designers need to know how to sell ideas, themselves and product. That’s the business. Know the potential of how you and your products can affect the world around you…a good piece of design and a good designer emote something to others.” He suggests that designers looking to get media attention pitch stories rather than products to editors. “Everyone like exclusives—pitch a different angle to each editor you approach.”

|

The Call, Phase Two

As Miller begins his second year in business, he has set his sights on building a “more powerful financial scheme and a stronger, larger and more diverse network of industry relationships.” A national design competition held during fall 2003 developed into a relationship with the new Manhattan design manufacturing and distribution firm, Conduit, the umbrella company for Six Socks and Six Chocolates. Two of Miller’s furniture objects—a plastic chair and a floor lamp with a foam shade—were selected from the competition to be part of Conduit’s inaugural fall 2004 collection, which includes pieces by Constantin Boym, Tobias Wong and Miller’s fellow Surface 2003 T.A.G. Team member, Josh Owen. When the Conduit collection premiers during ICFF 2004, Miller will have doubled his 2004 goal of getting one object into circulation.  His seemingly passive plan of putting his objects out for others to see and experience appears like a non-plan because it doesn’t involve the conventions common in American business. But Miller’s approach to building his firm not only involves a keen understanding of how to bring to market what a manufacturer wants to produce, but also what consumers actually need. His seemingly passive plan of putting his objects out for others to see and experience appears like a non-plan because it doesn’t involve the conventions common in American business. But Miller’s approach to building his firm not only involves a keen understanding of how to bring to market what a manufacturer wants to produce, but also what consumers actually need.

Although part of him wishes that he had written a formal business plan for organizing his activities and outlining his strategies with “goals that translate into realistic outcomes to sustain and develop” his business, Miller feels this would have been a mistake. “I’m only learning now about what things are getting me traction, which makes the present very much in flux. The lesson that I taught myself has been that by putting something out there, you get tremendous feedback—it’s never going to be perfect, it’s never going to be ready, there’s never going to be the perfect client—but if you don’t make any goal, you will never achieve anything.”

|

Other articles in the series:

Part 1: Green Desire (Profile of Jamie Salm)

From the Trenches is a six-part series that examines the methods contemporary design firms use to communicate their business mission and design philosophy through their marketing initiatives and public relations activities. The first five installments will each feature a firm at a particular stage of evolution. Installments one and two will present design firms under two years old, the first operated by a recent design school graduate, the second by an established industry pro now striking out on his own. Subsequent installments will look at firms between 5-and-7 and 10-and-12 years old, and lastly, a firm with more than 15 years of industry experience. The final installment will sum up the previous five with the intent of discussing the reasons behind the current marketing and publicity methods contemporary design firms use with an eye towards comparing these methods against those employed by firms who are battling for a competitive edge in other innovative industries.

Philadelphia-based journalist Joseph Dennis Kelly II specializes in covering architecture and design. A graduate of the University of the Arts and the Home & Design editor of Philadelphia Style magazine, his work has appeared in I.D. (International Design), Metropolis (forthcoming), Architectural Record, Architecture, World Architecture, Interior Design and Clear. He also provides strategic writing and editing services to clients working internationally in the architectural and design fields. He can be reached at jdkelly.kellycomm@verizon.net

> back to top

> back to core

|

|

![]()

Johndonnell, known for favoring designers with an innovative perspective of—and distinctive approach to—design, agrees with Chan, writing that “young designers today have been swayed by the new sense of celebrity that has wrapped many ‘big’ designers. Young designers seem preoccupied with creating logos and marketing materials, and not enough with the prioritization of their product. I can’t tell you how often I get a great presentation of marketing materials for a crap product—a 3D rendering of something that is essentially slick shiny crap. Designers need to have a business strategy. Knocking on the door of manufacturers doesn’t count. That’s simply one element of a plan. Designers these days seem to carry themselves like a garage band, carrying demos, playing a gig here and there, then hoping to ‘be discovered.’ Rarely does it work this way. Designers need to know how to sell ideas, themselves and product. That’s the business. Know the potential of how you and your products can affect the world around you…a good piece of design and a good designer emote something to others.” He suggests that designers looking to get media attention pitch stories rather than products to editors. “Everyone like exclusives—pitch a different angle to each editor you approach.”

Johndonnell, known for favoring designers with an innovative perspective of—and distinctive approach to—design, agrees with Chan, writing that “young designers today have been swayed by the new sense of celebrity that has wrapped many ‘big’ designers. Young designers seem preoccupied with creating logos and marketing materials, and not enough with the prioritization of their product. I can’t tell you how often I get a great presentation of marketing materials for a crap product—a 3D rendering of something that is essentially slick shiny crap. Designers need to have a business strategy. Knocking on the door of manufacturers doesn’t count. That’s simply one element of a plan. Designers these days seem to carry themselves like a garage band, carrying demos, playing a gig here and there, then hoping to ‘be discovered.’ Rarely does it work this way. Designers need to know how to sell ideas, themselves and product. That’s the business. Know the potential of how you and your products can affect the world around you…a good piece of design and a good designer emote something to others.” He suggests that designers looking to get media attention pitch stories rather than products to editors. “Everyone like exclusives—pitch a different angle to each editor you approach.” His seemingly passive plan of putting his objects out for others to see and experience appears like a non-plan because it doesn’t involve the conventions common in American business. But Miller’s approach to building his firm not only involves a keen understanding of how to bring to market what a manufacturer wants to produce, but also what consumers actually need.

His seemingly passive plan of putting his objects out for others to see and experience appears like a non-plan because it doesn’t involve the conventions common in American business. But Miller’s approach to building his firm not only involves a keen understanding of how to bring to market what a manufacturer wants to produce, but also what consumers actually need. After graduation, however, looking for direction, experience and a regular paycheck, he turned to the world of design consulting, He was soon hired as the first full-time employee of a start-up design consultancy in an office so cramped he literally rubbed elbows with the firm’s principal, Eric Chan. Working closely with a talented designer like Chan has its benefits, and over the years Miller helped build ECCO into what is today a well-respected 15-member team of top-notch designers.

After graduation, however, looking for direction, experience and a regular paycheck, he turned to the world of design consulting, He was soon hired as the first full-time employee of a start-up design consultancy in an office so cramped he literally rubbed elbows with the firm’s principal, Eric Chan. Working closely with a talented designer like Chan has its benefits, and over the years Miller helped build ECCO into what is today a well-respected 15-member team of top-notch designers.

The Miller Greene experience took him to a new level as a designer. A self-proclaimed perfectionist, Miller was delighted to have broken free of his inhibitions, if only for a few months, and to have lived the dream of a solo design career, an aspiration he had since he first came upon the field of industrial design, when he found, in the library of his West Chester (NY) high school, a book on Raymond Loewy. After reflecting on the Miller Greene venture and reconnecting to the passion he felt when he first read about Loewy, he knew he was on his path, a fact that was affirmed when his Miller Greene modular seating unit won an I.D. Magazine 1997 design award.

The Miller Greene experience took him to a new level as a designer. A self-proclaimed perfectionist, Miller was delighted to have broken free of his inhibitions, if only for a few months, and to have lived the dream of a solo design career, an aspiration he had since he first came upon the field of industrial design, when he found, in the library of his West Chester (NY) high school, a book on Raymond Loewy. After reflecting on the Miller Greene venture and reconnecting to the passion he felt when he first read about Loewy, he knew he was on his path, a fact that was affirmed when his Miller Greene modular seating unit won an I.D. Magazine 1997 design award. During ICFF 2003, he showed his work in yet another storefront-style exhibition, this time in a group exhibition at the Chelsea Hotel organized by the Downtown group and entitled “Downtown at the Chelsea Hotel.” And while this show again generated much enthusiasm for his work, it was his selection to Surface Magazine’s 2003 T.A.G. Team and the inclusion of his work in Surface’s 2003 Salone del Mobile and ICFF installations—as well as Surface’s special ICFF 2003 off-site show at a Chelsea museum—that really catapulted Miller onto the industry’s radar screen as an important emerging solo designer. Riley Johndonnell, brand creative director for Surface Magazine, writes via email that he selected Miller for Surface’s 2003 T.A.G. Team because Miller “seems less concerned with embedding his ego into the design object,” adding that in Miller’s work “function, innovation and beauty come first…It’s very pure design where aesthetic is influenced by the function. His signature does come through in the design, but not in a forced way. His pieces seem to speak of a process: in each piece you can see solutions to problems, you can see the designer’s thought process.” These exhibitions of Miller’s objects caught the eye of Joey Tessalona, design director at Clinton’s Felissimo Design House. Tessalona, who calls Miller a "great upcoming designer," selected Miller’s aluminum bed for inclusion in Felissimo’s recent “Life Symphony” exhibition.

During ICFF 2003, he showed his work in yet another storefront-style exhibition, this time in a group exhibition at the Chelsea Hotel organized by the Downtown group and entitled “Downtown at the Chelsea Hotel.” And while this show again generated much enthusiasm for his work, it was his selection to Surface Magazine’s 2003 T.A.G. Team and the inclusion of his work in Surface’s 2003 Salone del Mobile and ICFF installations—as well as Surface’s special ICFF 2003 off-site show at a Chelsea museum—that really catapulted Miller onto the industry’s radar screen as an important emerging solo designer. Riley Johndonnell, brand creative director for Surface Magazine, writes via email that he selected Miller for Surface’s 2003 T.A.G. Team because Miller “seems less concerned with embedding his ego into the design object,” adding that in Miller’s work “function, innovation and beauty come first…It’s very pure design where aesthetic is influenced by the function. His signature does come through in the design, but not in a forced way. His pieces seem to speak of a process: in each piece you can see solutions to problems, you can see the designer’s thought process.” These exhibitions of Miller’s objects caught the eye of Joey Tessalona, design director at Clinton’s Felissimo Design House. Tessalona, who calls Miller a "great upcoming designer," selected Miller’s aluminum bed for inclusion in Felissimo’s recent “Life Symphony” exhibition.