|

The dust from James Dyson's recent resignation as the chairman of the board at the London

Design Museum is just beginning to settle. Over the past decade Dyson, the vacuum cleaner entrepreneur and frequent television pitchman, cleaned up in the home appliance sector with his wildly successful DC02 (a canister vacuum

for pullers), and his follow up DC07 (an upright vacuum for pushers). The most critical contribution Dyson made to the industry was maintaining suction by doing away with filter bags. He pioneered root cyclone technology, a powerful

and patented system for spinning out dirt into a plastic catch. The vacuum cleaner wasn't Dyson's first hit. Years earlier he was recognized for both his Sea Truck and the Ballbarrow as well as other furniture and product designs.

Dyson's generosity is almost as well known as the number of prototypes he tested before perfecting his vacuum (5,127 if you weren't sure). He plowed his success back into the design community by supporting everything from breast

cancer to a major education center at the Design Museum where he was appointed a trustee in 1997 and chairman of the board in 1999. [Read the October 2002 Core77 interview here.] The dust from James Dyson's recent resignation as the chairman of the board at the London

Design Museum is just beginning to settle. Over the past decade Dyson, the vacuum cleaner entrepreneur and frequent television pitchman, cleaned up in the home appliance sector with his wildly successful DC02 (a canister vacuum

for pullers), and his follow up DC07 (an upright vacuum for pushers). The most critical contribution Dyson made to the industry was maintaining suction by doing away with filter bags. He pioneered root cyclone technology, a powerful

and patented system for spinning out dirt into a plastic catch. The vacuum cleaner wasn't Dyson's first hit. Years earlier he was recognized for both his Sea Truck and the Ballbarrow as well as other furniture and product designs.

Dyson's generosity is almost as well known as the number of prototypes he tested before perfecting his vacuum (5,127 if you weren't sure). He plowed his success back into the design community by supporting everything from breast

cancer to a major education center at the Design Museum where he was appointed a trustee in 1997 and chairman of the board in 1999. [Read the October 2002 Core77 interview here.]

In deciding to resign his position, Dyson accused the museum (and perhaps museum director Alice Rawsthorn as well) of "betraying the proper ideals of its founder," "ruining its reputation," and of "becoming

a style showcase" while neglecting its role to "uphold its mission to encourage serious design of the manufactured object." Dyson's accusation that the Design Museum was pursuing empty style over substance is a topic

of debate. Regardless, empty style has lead to twenty percent rise in visits, a ninety percent rise in education trips, and a fifty-six percent rise in membership at the museum.

There is an upshot from all of this. Dyson has opened a valuable portal that leads both back to the late nineteenth century and to a bright future of next-century design. Best of all, it places one of design's most cherished axioms

back into play, that form follows function. Stepping inside this new gateway, we have an opportunity to refresh a conversation that not only establishes where we have been and where we stand today, but also informs the ultimate

direction for the unfolding ribbon of human-centered accomplishment.

In 1896, Louis Sullivan published his article, The

Tall Office Building Artistically Considered in Lippincott's Magazine. His well-crafted elegy to nature and natural systems as they relate to building was one of the earliest attempts to define how his generation's next

century architectural systems should be implemented. These were the very systems that would allow the design and construction of much taller buildings and would lead to contemporary skyscrapers. Sullivan, realizing that new technology

would radically change his profession and the urban landscape, quickly stamped the design community with an enduring adage that would last over one hundred years. He wrote, "Whether it be the sweeping eagle in his flight, or

the open apple blossom, the toiling workhorse, the blithe swan, the branching oak, the winding stream at its base, the drifting clouds, over all the coursing sun, form ever follows function, and this is the law." In 1896, Louis Sullivan published his article, The

Tall Office Building Artistically Considered in Lippincott's Magazine. His well-crafted elegy to nature and natural systems as they relate to building was one of the earliest attempts to define how his generation's next

century architectural systems should be implemented. These were the very systems that would allow the design and construction of much taller buildings and would lead to contemporary skyscrapers. Sullivan, realizing that new technology

would radically change his profession and the urban landscape, quickly stamped the design community with an enduring adage that would last over one hundred years. He wrote, "Whether it be the sweeping eagle in his flight, or

the open apple blossom, the toiling workhorse, the blithe swan, the branching oak, the winding stream at its base, the drifting clouds, over all the coursing sun, form ever follows function, and this is the law."

Forgiving Sullivan his baroque (even ornamental) language, his treatise was not the first to rationalize form and function. Around 1750,

a Jesuit monk in Venice, Italy named Father Carlo Lodoli questioned the overuse of ornament and put forward his own tract that nothing should be put 'on show' that was not 'in function.' Sullivan may or may not have been aware of

Father Lodoli's theories (referred to by some as the Socrates of architecture). Still, Sullivan's attempt to define a "true normal type" was successful, and became a torch carried into the twentieth century and held aloft

by early modernism. What exactly constitutes a true normal type has always been a topic of disagreement. The early twentieth century saw designers re-purposing and continually redefining Sullivan's idea to suit their own concept

of the idiom. In 1908, Austrian architect Adolph Loos wrote an article titled Ornament and Crime that began a European anti-ornamentation movement. Walter Gropius adopted some of Sullivan's ideas into the Bauhaus and made

reference to the axiom noting in a 1934 London lecture that the Bauhaus seeks to "derive the form of an object from its natural functions and limitations." The industrial designer Walter Dorwin Teague wrote in 1940 that

"the function of a thing is its reason for existence, its justification and its end," in his book Design This Day. Forgiving Sullivan his baroque (even ornamental) language, his treatise was not the first to rationalize form and function. Around 1750,

a Jesuit monk in Venice, Italy named Father Carlo Lodoli questioned the overuse of ornament and put forward his own tract that nothing should be put 'on show' that was not 'in function.' Sullivan may or may not have been aware of

Father Lodoli's theories (referred to by some as the Socrates of architecture). Still, Sullivan's attempt to define a "true normal type" was successful, and became a torch carried into the twentieth century and held aloft

by early modernism. What exactly constitutes a true normal type has always been a topic of disagreement. The early twentieth century saw designers re-purposing and continually redefining Sullivan's idea to suit their own concept

of the idiom. In 1908, Austrian architect Adolph Loos wrote an article titled Ornament and Crime that began a European anti-ornamentation movement. Walter Gropius adopted some of Sullivan's ideas into the Bauhaus and made

reference to the axiom noting in a 1934 London lecture that the Bauhaus seeks to "derive the form of an object from its natural functions and limitations." The industrial designer Walter Dorwin Teague wrote in 1940 that

"the function of a thing is its reason for existence, its justification and its end," in his book Design This Day.

While the globetrotting International Style made its way from Indiana to India, form surely followed function. But with pure modernism about to be relegated to an MTV I Love the 50's episode, we should take note of the British

architectural critic Rayner Banham who referred to Sullivan's axiom as an "empty jingle" back in 1960. Banham was ahead of his time. Today form no longer needs to follow function, and ornamentation is back with a vengeance.

It's not the artistic embellishments that Sullivan and Loos railed against, but an ornamentation born of new materials and new technology. The irony here is that it was the new technologies of the late nineteenth and early twentieth

centuries that moved Sullivan to originally excoriate ornament, and it is that same new technology that has brought it back.

Materials and engineering advances have allowed architects and designers to fashion new shapes and forms, layering them over

simplified, high-strength frames. We entertain endless possibilities and now inhabit what Joe Rosa (SFMOMA curator of architecture and design), would call "folds, blobs and boxes." Ornamented skin is in. Frank Gehry's

titanium, Herzog and De Meuron's copper, and Rem Koolhas' metal and glass origami folds are just a few of the endless new patinas architects are using to add decoration to computer- and engineering-aided forms. With skin taking

on revitalized importance in architecture, buildings are no longer simply machines for living. They hold multiple meanings, even becoming brand extensions for the likes of Guggenheim, Prada, Disney and others. How a building reflects

cultural values is again as important as how it functions. Materials and engineering advances have allowed architects and designers to fashion new shapes and forms, layering them over

simplified, high-strength frames. We entertain endless possibilities and now inhabit what Joe Rosa (SFMOMA curator of architecture and design), would call "folds, blobs and boxes." Ornamented skin is in. Frank Gehry's

titanium, Herzog and De Meuron's copper, and Rem Koolhas' metal and glass origami folds are just a few of the endless new patinas architects are using to add decoration to computer- and engineering-aided forms. With skin taking

on revitalized importance in architecture, buildings are no longer simply machines for living. They hold multiple meanings, even becoming brand extensions for the likes of Guggenheim, Prada, Disney and others. How a building reflects

cultural values is again as important as how it functions.

In the case of product and furniture design the same holds true. Engineering advances have made it possible for us to fit function into any shape, size or format, relegating it to an afterthought. Today's user experience is highly

personalized, with consumers choosing products based on how they fit within their lifestyles in an 'anything is possible' environment.

The role of the consumer as a driving force behind form and function has upset Sullivan's apple cart. While in the past these decisions were the bailiwick of professional designers, the dual roles of want and need have given individuals

new powers. Want and need directly infect and affect form and function. Function, ideally, is based on need. (To see the 'design of need' in action you can look at the work of Samuel Mockbee and the Rural

Studio.) It doesn't dazzle or sparkle, but does keep less fortunate people warm and dry. The 'design of want' is style based. And with a global economy that continues to create wealth, we have unlimited opportunities to feed

our wants; the design community has no choice but to respond to market forces.

The new exhibition, Glamour, at SFMOMA (curated by Rosa) brings many of these ideas into sharp focus. Rosa deftly positions important mid-century

archetypes (now considered reactions against high modernism through the use of simple ornamentation) against the newest digital designs with their heavy layers and tactile surfaces. Rosa draws a comparison and a timeline between

the old and new. In doing so he elevates the hidden value of our current diamond-encrusted design excesses. Using these objects to define and herald the revived importance of glamour, Rosa is also commenting on the century-old adage

of form following function. The show relies heavily on innovative technology as the genesis for many of the objects on display, but there is little discussion of the role it plays in design and production decisions. By no means

is this an indictment of the curator. In fact it is just the opposite. It is added proof that style (or in this case 'glamour'—the two are only different in the minds of design theoreticians and power shoppers) has again trumped

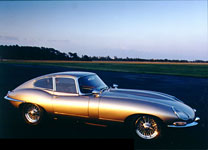

function.  James Dyson raised similar concerns about the lack of technical information in regard to a Jaguar exhibition

at the Design Museum. He wanted visitors to understand how aerodynamics and engineering informed the now classic bubble cockpit. (Rosa, as it happens, included a candy apple red Jaguar E-type coupe in his show.) The bottom line

is that we've lost interest in how and why things are made in favor of how objects make us feel. Image is everything and function, based on widely accepted science and technology, is assumed. James Dyson raised similar concerns about the lack of technical information in regard to a Jaguar exhibition

at the Design Museum. He wanted visitors to understand how aerodynamics and engineering informed the now classic bubble cockpit. (Rosa, as it happens, included a candy apple red Jaguar E-type coupe in his show.) The bottom line

is that we've lost interest in how and why things are made in favor of how objects make us feel. Image is everything and function, based on widely accepted science and technology, is assumed.

James Dyson, a modern day Sysiphus, is fighting an uphill battle until he accepts that widespread penetration of technology into multiple facets of our lives leads to disinterest in the process of how and why things function the

way they do (remember those 5127 prototypes?). He is also unwilling to accept or understand the power of the consumer and the duality of want and need. Dyson's grounding in functionalism is apparent in the very fact that people

don't want a vacuum cleaner; they need one.

We are a society prone to taking things for granted. Louis Sullivan feared what would happen when architects over-personalized the access that technology provided. In response to his fears, he created a well-followed paradigm that

a century of progress has made obsolete. The debate about whether form follows function should finally be put to rest. But let's begin again with a new idiom and a new discourse on design. Style ever follows engineering! Or does

it?

Amos Klausner is the director of the Museum of Contemporary Art at the Luther Burbank Center in Santa Rosa, California.

|

![]()