|

![]()

> archived articles

> write for core! be famous!

|

Interview: Roy Thompson, senior Designer at Continuum by Bob Parks |

|

|

BOB PARKS: What's the most important part of the design process? ROY THOMPSON: I like to talk to people, so the research is one of the fun parts. And you have to do a lot of research. A client comes to a consultancy for an outside opinion. You need to get into it deep enough that you're sure of what you're recommending. If you present a number of concepts on a table, you need to have a solid rationale for each. BOB: Can you give an example? ROY: When Numark, a company that makes DJ gear, came to us, they'd just been bought by new owners. The president wanted to do something different. Before this, DJ mixers had just been basic flat aluminum plates with a few knobs and stickers applied. It was hard to do any variation. But Newmark wanted an entire line of DJ equipment. We started by talking with DJs. You can't call up 1-800-DEE-JAYS, so we had to go club hopping for a couple weeks straight, hanging out at the booth. We went to record stores and bought them meals and let them chew on our ears for a while. We ran into a strange point where hey all said that they didn't care what a mixing board looked like, as long as it was durable, reliable, and had good sound. Meanwhile, these guys are wearing like custom Oakley sunglasses with yellow lenses and they're telling us they don't care what the gear looks like. So we turned a corner--instead of asking them what their equipment looks like we asked what kind of car they'd like to drive. They knew their stuff. The answers were like: "Mercedes is cool, but I'd have to get some nice rims for it--just to make it a little different." We used that data to influence the forms and details in the product. It turned out a little more BMW than Mercedes. If it just looked different, but didn't offer any new benefits however, a DJ wouldn't buy it at all. As long it has all the quality and durability that they expect, you can make a cool, funky look, because then the new identity will be connected with great quality and great sound. Numark came out with new technologies to make sure we had substance behind the surface treatment. But we also looked at the DJ's environment. A big thing is spills. Most board are flat. We designed a bump detail into the surface so that with a light spill, the liquid would flow away from the mixer. Also, in a dimly lit environment this bump language helps you see the buttons. We found out that battle DJs spend hours practicing techniques of scratching and mixing, and with cheaper mixers, the knobs literally break off. What a lot of them do is go to the electronics store, wait until no one's looking, and pull a knob off of the floor model. Guys showed us they had a bag of knobs. So we designed a mixer with the knobs below the faceplate, so you can't pull them off. And that way you don't have to take off 20 knobs just to take the face plate off. |

BOB: So you like the research. Why is it important? Doesn't the client know the customer best? ROY: Quite often clients come to us, tell us they want one thing, but as soon as we get into the research, we realize that they might need something else. A big part of our process is getting in touch with the client ahead of time. We want to ask them, "What peg do we need to make it fit," instead of forcing what we think is the right peg. Once we start doing some research and getting into the client, we find out what they thought they wanted isn't the correct solution. When you work for a consultancy, the client comes to get an outside opinion. A consultancy does a variety of work. Sometimes you work with a company that does one product category exclusively--it's like having blinders on. We can step back and not have deal with the internal politics of the company we're working on. If we're designing a faucet, we do more than facets, but a designer who's working for Kohler, well that's all they do. We spend the time to do the research to be sure of the answer. A lot of time you start in the kickoff meeting of a project and you'll have a gut feeling about a project. Sometimes that feeling is wrong. The research can back up what we're recommending. We get out on the street, we do ethnographic studies, videotape people using the products. We don't present a dozen concepts on a table and say, "Well, which one do you like?" | |

|

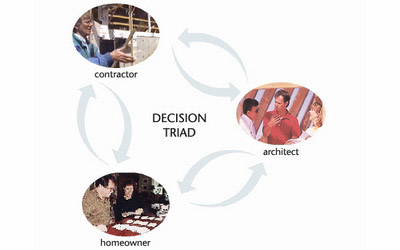

BOB: What's that first client meeting like when you come back to them with some research? ROY: One thing we do is present the client with a list of attributes for their future product--it has to be rugged, smart, precise, etcetera. We do that with a system called the "Visual Library." Once a month, the whole Continuum office gets together in one room--the receptionist, designers, the people from accounting. We usually have a couple of pizzas. There have been a bunch of products that have been designed to appeal to designers. One way to avoid that is to make sure you get regular people in the Visual Library meetings, people who aren't infatuated with whatever Audi's doing at the moment. It's a way to get their opinions on design. We'll take a word like "Trustworthy." People bring in images from books, magazines, the Web that associate with that word. We even solicit sounds, images, textures, and materials to better understand the qualities of the word. Then we create an inspiration board of "Trustworthy" images--maybe pictures of a golden retriever or Chevy truck, things like that. When you're thinking about pure styling, you look at these boards and try to incorporate these elements into the product. So instead of doing a bunch of sketches, we make sure a client buys off on those qualities before we start sketching. That way we don't get the VP of marketing picking a design because it uses his favorite color. It's a way to take the emotion out of it, and decide on a logical level. Then the consumer will pick it up on an emotional level. We've done "Robust," "Fast," "Cute," "Sporty." "Sporty" has a lot of "Cute" to it. Look at the a Miata, for example. BOB: How did you get started in ID? ROY: I didn't know anything about industrial design growing up. I was a kid from Brooklyn. I made graffiti in junior high. My tag was Spice One. Looking back on it, graffiti almost becomes an addiction--ugh, this sounds like therapy talking about it--but running around with a can, it's like you see a wall and you have to put your mark on it. And the bigger and cleaner the surface is, the more you got to put your mark on it because people are going to see your name up there and say, "Dang." And the other part I liked about it was doing large pieces, which is essentially graphic design, typography, color, layout, format. That's what led me down this path. I knew I wanted to do something creative in college. When I took a graphic design course it college, it clicked--this is legal graffiti. I went to RISD, studied graphics and loved it, but a lot of the stuff you do in graphics has a limited life span and the results are too fleeting. You might do a poster for a movie that runs for a month or two. I got into packaging, but I wasn't content with putting a label on a box. BOB: What was the first product development project you worked on? My graduate thesis was entitled "Power to the People." That was a great project. At the time, technology design was geared toward the business professional, toward middle-class professionals and up. The opportunity was to get things to the everyday consumers. How could I design for people who ride the bus to work? One thing about approaching bus stops and starting to talk to people--they think you're some kind of weirdo. The first thing I had to do was break the ice and make them understand that I'm not some kind of nut. I told them I was doing a project on technology. At first they couldn't give you any ideas because they don't know what they want. People only understand what they're familiar with. And then, where I could, I said, "What do you have in your purse?" "What's in your wallet?" I don't know who doesn't have a stack of receipts in there, or the thousands of cards you get from Stop and Shop or pharmacy. I asked them, "What are the problems of your life." "It's hard to keep track of money," was one answer, "Where does it go?" From there I designed some concepts that addressed those needs. It won a few awards. BOB: I heard you recently worked on some successful residential windows. How did you apply your research skills to that project? ROY: Andersen is about quality windows that are really weather-tight. But there were a lot of inexpensive vinyl and aluminum windows coming into the market, and more and more consumers were buying them. This was the shift going on. We did a whole bunch of research, and figured out that Andersen makes a 30-year guarantee, but people who build now only expect to be in their house for 5 - 10 years. That guarantee isn't as valuable. You can either get a house with Andersen windows, or you can build an additional floor with the money you save on cheap windows. Once the sticker comes off, not many people would know what kind of windows you have. People were trading down to get the whirlpool Jacuzzi tub. Andersen didn't want to water down the brand. They wanted a product with the same quality for a different price. They had to do something, but they didn't know how. They only know how to make a good window. They didn't have the structure to know what people look for when they buy windows, and they wanted to take some business away from the cheaper competitors. We talked to contractors, architects, homeowners, wives, husbands. We went to Home Depot and stationed ourselves in the isles.  We tried to design a window to meet everyone 's needs for a very strict price limit. We had to come up with a lot of ideas that would save money on the manufacturing process. For weather-resistance, we tried to eliminate the seams wherever possible, so dirt or water wouldn't get into the seam. For the first prototype, we made the best looking window we possibly could. It was 60 percent more than our price target. But then we had something to aim for. It helped us figure out what the constraints were. We found that people had to see the wood, and that wood was going to add another two dollars on each window. But everyone saw that that money added so much to the window. The world is full of these kinds of compromises. But we didn't want a plain looking window. Andersen was only going to make one window, so we designed a window we call a "considered neutral." We wanted to add just enough detail to make it look considered--where it would look fine on a Victorian, colonial, or modern house. We still wanted the architect and the builder to be happy. BOB: You can't make a more permanent statement than windows. ROY: Yup, when people drive by the house, I want them to say, "Now,

that's a gorgeous house. Who designed that?" Bob Parks (bobparks-at-yahoo.com) writes about industrial design, consumer technologies, and the outdoors for such magazines as Business 2.0, Outside, and Wired. He lives with his wife, Eileen, and son and daughter, Archer and Lucy, in Brattleboro, Vermont. |

|