- Sponsored

From Imperfection to Innovation: How Digital Materials Support Sustainable Design

A conversation with Nicolas Paulhac, Director of 3D Content at Adobe Substance

This post is presented by the K-Show, the world's No.1 trade fair for the plastics and rubber industry. Visionary developments and groundbreaking innovations will again lead the industry into new dimensions at K 2025 in Düsseldorf, Germany.

Chris Lefteri: Nicolas, before we dive in, tell us a bit about yourself and what you do at Adobe.

Nicolas Paulhac: I'm the Director of 3D Content at Adobe Substance. My background spans industrial design and CMF (Color, Material, Finish), where I focused on how products are made and how various industrial processes shape material transformation.

At Adobe Substance, we offer a suite of five specialized applications for material authoring, texturing, and staging—empowering 3D artists and designers across diverse industries to create digital materials, apply them to products, and visualize their designs. My role involves leading content production within these apps and curating ready-to-use assets for our Substance 3D Assets library, which provides the foundational elements creators need for their 3D projects.

Nicolas Paulhac, Director of 3D Content at Adobe Substance © Adobe Inc. 2025 – All rights reserved

Nicolas Paulhac, Director of 3D Content at Adobe Substance © Adobe Inc. 2025 – All rights reserved

Chris Lefteri: Perfect! And how do you bring the world of real materials into the Adobe software?

Nicolas Paulhac: Digital material creation can be approached in two main ways, each offering unique advantages. You can scan a real physical surface or create textures fully digitally.

Scanning, involves capturing real-world materials using a material scanner. It ensures high fidelity and precision by generating texture maps that reflect how the material reacts to light through key properties such as color, glossiness and surface relief. It's ideal for replicating materials with accuracy and realism.

Materials can also be built entirely from scratch using procedural tools. This method offers maximum flexibility and control, enabling creators to define every aspect of the material's behavior and appearance without relying on physical samples.

These methods are not separate but complementary to each other. Designers can start with a scanned material and then apply additional effects—modifying color, adding surface details, or introducing patterns not present in the original sample. This approach allows for creative freedom while maintaining a strong link to the physical reference, essentially crafting a personalized "material behavior".

At Adobe Substance, we utilize both methods to produce textures. Each material in the 3D Assets library is a living asset designed to be personalized. Each material, through its exposed parameters that users can modify, acts as a mini-library capable of generating infinite variations of itself—whether in terms of color, surface grain, glossiness, pattern, and more. For CMF designers specifically, it can act as a kind of digital fab lab. This empowers artists and designers to build tailored digital materials that are both expressive and production-ready by preserving coherence with real-world material behavior.

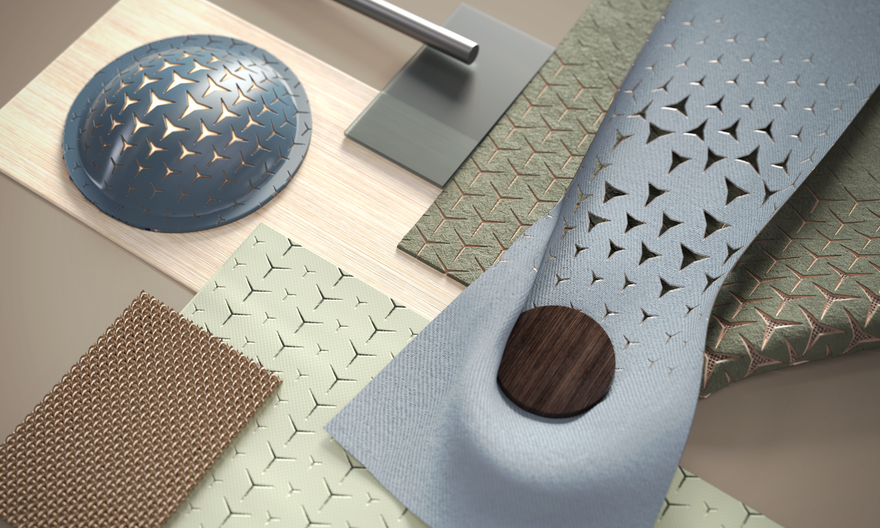

© Adobe Inc. 2025 – All rights reserved

© Adobe Inc. 2025 – All rights reserved

Chris Lefteri: And that Fab Lab is relating back to the way the materials, in the real three-dimensional sense, get processed?

Nicolas Paulhac: When there is a visual impact of the process on the surface, which is very often the case, yes. We begin by studying the visual properties of physical samples to reproduce them as faithfully as possible. But we don't stop there. We analyze the forming processes—examining how each production step influences the final look and feel of the material. By connecting these insights to finishing techniques, we can introduce meaningful customization parameters into the digital material. It's a way of embedding process awareness into the material itself, making it not just a visual replica but a customizable digital asset.

© Adobe Inc. 2025 – All rights reserved

Chris Lefteri: So, you must have a fantastic physical materials library?

Nicolas Paulhac: We collect samples, indeed—but not just physical ones. Our references span a wide range of formats, including images, mood boards, color palettes, and technical documentation. Depending on the material or process we aim to recreate, we have collaborated on specific collections with material suppliers, consulted existing resources, or studied real products.

In some cases, we even fabricate custom samples specifically to create digital materials. This allows us to capture larger surface areas or to isolate individual stages of a finishing process—creating each stage separately. By doing so, we gain precise control and realism when digitally reconstructing the material.

Chris Lefteri: And how do you stay updated with new materials, technologies and processes?

Nicolas Paulhac: Well, it involves staying up to date with trends in product and CMF design. We approach it with a segmented lens—by industry and product category. We observe how materials evolve across domains to ensure our digital content remains relevant and forward-looking.

When it comes to manufacturing, we engage with model makers and material engineers, especially when we need to understand how things are made.

Sustainability trends are very interesting to us. Eco-designed materials are part of our area of interest— even if, for now, our focus is on making their digital twins visually realistic. We believe digital tools have a vital role to play here—supporting sustainable innovation at multiple levels.

A great example is our collaboration with Chris Lefteri Design for the 3D Assets library, which attempts to show how digital materials can support early-stage creative exploration. Whether it's advanced technologies like reactive surfaces—thermo-bimetals or auxetics—the digital medium allows us to mimic desirable finishes and potential applications long before physical prototypes exist.

© Adobe Inc. 2025 – All rights reserved

© Adobe Inc. 2025 – All rights reserved

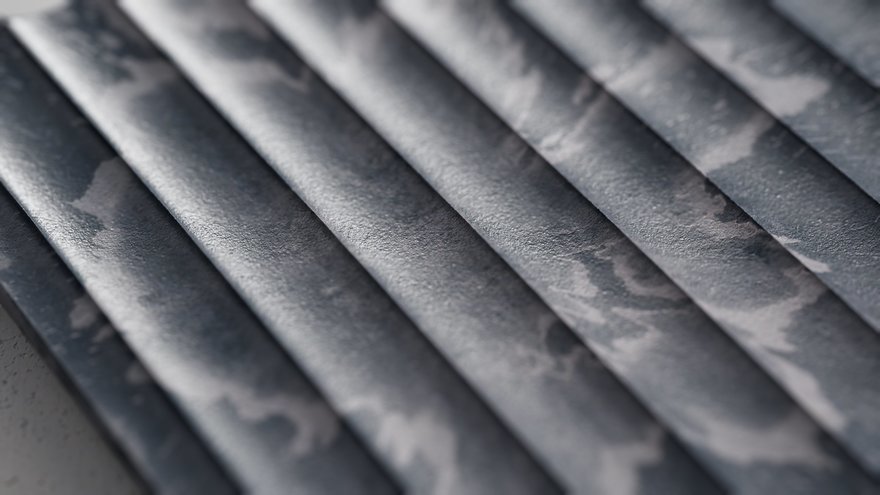

Similarly, our visual explorations around plastic injection processes for the K-Show enabled us to pre-visualize new effects linked to the use of fillers. This opens creative opportunities to make imperfection and transformation desirable—turning technical constraints into expressive material qualities for design.

Chris Lefteri: Yes, this most recent collaboration was looking at sustainability as a new way to realise the surface or composition of a material and to somehow represent that digitally. Was it a challenge for your team to work on our collaboration, or generally on dealing with unperfect materials?

Nicolas Paulhac: It was a truly stimulating challenge. The brief on composite plastics gave us the opportunity to explore not only how to visualize these effects with realism, but also how to parameterize each technical attribute to animate transitions between different surface states.

It's a perfect example of what I mentioned earlier: building each effect digitally and procedurally, then combining them into a cohesive material experience. One of the key challenges was controlling the flow effect when mixing different components—capturing realistic dispersion patterns, the kind of surface visuals that emerge as fillers propagate and accumulate progressively. This type of work shows how digital materials can go far beyond static textures — they become dynamic, expressive tools for storytelling in CMF design.

Chris Lefteri: So would the user of the software be able to control this level of tunability, in terms of color, movement and flow of the material?

Nicolas Paulhac: Yes, users will have control over most of these aspects. Of course, there are the basic parameters—like color and glossiness—that come standard with every material. But in this case, the user can also control the size and amount of filler added into the formula, and adjust the parameters that influence distribution, density, and growth. These changes directly affect the resulting patterns, giving the user the ability to shape how the material evolves visually.

© Adobe Inc. 2025 – All rights reserved

© Adobe Inc. 2025 – All rights reserved

© Adobe Inc. 2025 – All rights reserved

© Adobe Inc. 2025 – All rights reserved

Chris Lefteri: Are you seeing more industries adopting and engaging with digital materials outside the traditional ones of automotive and product design?

Nicolas Paulhac: Yes, we're definitely seeing a wide range of industries embracing digital materials beyond the traditional domains of automotive, architecture, and product design. Industries such as fashion and consumer packaged goods, to name a few, are increasingly adopting digital solutions—not just for the product itself, but across every aspect of the design and visualization process. For example, even the contents of a package now need to be visualized with realism.

This shift opens new opportunities for designers to streamline workflows, enhance visualization, and maintain consistency between digital and physical outputs. It's largely driven by the need for faster iteration, cost reduction, sustainability goals, and the expanding role of digital twins—from early-stage development to marketing visualization.

Chris Lefteri: Are you saying that individuals are using the software to develop food?

Nicolas Paulhac: Yes, it's connected to the design. It also plays a key role in accelerating the overall process. It helps bridge design and production with the marketing phase, allowing products to be showcased earlier to consumers. This is a major advantage of using 3D: it enables visualization at an earlier stage, in a faster and more cost-effective way compared to traditional methods like photo shoots.

Chris Lefteri: I was actually thinking of how chefs could use it to develop their recipes or food. Because a lot of this high-end food is very visual, it is more about the Instagram image than the food itself. So, chefs could use it to design texture, patterns or effects for instance?

Nicolas Paulhac: I believe that's one of the opportunities as we look ahead. A good example could be cosmetics—how do you accurately represent what comes out of the tube? Oils, serums, and other formulations need to be visualized realistically for marketing purposes. So why not use the digital medium to explore creative iterations in terms of design? It opens up new possibilities for visual storytelling and early-stage concept development, even before a physical prototype exists.

Chris Lefteri: And, for example — dare I say — even something like skin?

Nicolas Paulhac: This is actually a well-established practice in the world of games and film, known as "character art," where specialized artists focus on texturing human and non-human skin—whether realistic or stylized.

Thanks to the level of realism we can now achieve, new opportunities are emerging in other fields like Medical and healthcare. Being able to visualize not just skin but full anatomy in high detail is proving valuable—for example, one of the applications is training medical staff with virtual surgeries.

Chris Lefteri: Very interesting. Also, you now have the more futuristic imagery which doesn't even relate to a physical product – it is completely imagined. How do you approach this?

Nicolas Paulhac: A large part of the materials we create is dedicated to the game and VFX industries, where expressiveness and realism are key. The finality may differ across design disciplines but actually, the approach of creation isn't so different. Whether the material is real or imagined, it still needs to tell a story. It's about crafting what makes the material visually credible to the eye. We all go through the same instinctive reactions when we see a surface for the first time: is it soft or hard, reflective or matte, smooth or textured? These visual cues are essential to conveying emotion and materiality—how something is made, what it's made for, and what it could inspire in terms of application.

Substance digital materials are based on PBR—Physically Based Rendering—which means they accurately simulate how a surface interacts with light. With the Substance 3D applications, creators can design fully digital materials in a hyper-realistic way while maintaining control over key visual properties that matter in their field of expertise.

© Adobe Inc. 2025 – All rights reserved

© Adobe Inc. 2025 – All rights reserved

Chris Lefteri: How do you see the use of these digital materials and tools evolving in the future?

Nicolas Paulhac: Looking ahead, I believe digital materials and tools will become even more central to how industries design, validate, and communicate products. The goal isn't to position physical and digital materials as opposing forces in product creation, but rather to explore how they complement each other in the design process. By doing so, designers gain more creative freedom to visualize and communicate a design intention.

Digital twins will evolve into more dynamic and interconnected systems, enabling seamless transitions between virtual and physical workflows like behavior simulation, real-time feedback loops and predictive design.

As sustainability becomes non-negotiable, digital materials will play a key role in reducing waste, supporting more confident decision-making earlier in the process.

Chris Lefteri: My final question is, going back in time now, what's your favourite material memory from childhood?

Nicolas Paulhac: One of my favorite material memories from childhood is leather. My grandfather owned a small leather goods shop, and I spent countless hours watching him shape and repair leather bags. Observing the process—the way the material responded to heat, pressure, and tooling—sparked my fascination with how things are made. It was during those moments that I developed a deep interest in the transformation of materials, not just for their aesthetic qualities but also for their performance and surface effects. That early exposure continues to influence how I think about material design today.

NOTE: Chris Lefteri will be running design tours at the K Show on the 12th & 13th October. If you are interested in participating contact ktour@chrislefteri.com

K

{Welcome

Create a Core77 Account

Already have an account? Sign In

By creating a Core77 account you confirm that you accept the Terms of Use

K

Reset Password

Please enter your email and we will send an email to reset your password.