- Sponsored

Beyond the Launch: Why Designers Must Plan What Happens After

Former BMW design chief Chris Bangle argues for products designed for their "Second Existence" — creating jobs and redefining beauty

This post is presented by the K-Show, the world's No.1 trade fair for the plastics and rubber industry. Visionary developments and groundbreaking innovations will again lead the industry into new dimensions at K 2025 in Düsseldorf, Germany.

Chris Bangle (born 1956) is an American automotive designer who served as BMW's Chief of Design from 1992-2009. He now runs Chris Bangle Associates in Italy, working on luxury yachts, animation projects, and sustainable "Second Existence" design concepts.

Chris Bangle (born 1956) is an American automotive designer who served as BMW's Chief of Design from 1992-2009. He now runs Chris Bangle Associates in Italy, working on luxury yachts, animation projects, and sustainable "Second Existence" design concepts.

Chris Lefteri: Hi Chris, so, what are you up to these days?

Chris Bangle: I run a design consultancy, Chris Bangle Associates, in Northern Italy. We are about 10 people, and our workflow is mostly outside of Italy in fields that have to do with design such as product design, automotive design etc. It goes clear across the gamut of transportation and products. We also do a lot of workshops here that are for management, particularly things regarding creativity, brand design, managing creatives, etc.

Then recently we have also begun to get into kids' animation. This has opened up some worlds for us that we didn't know were relevant for design, but they are. Our research here ostensibly is to help create a fiction narrative that we try to animate. But in reality, it's helping us create a real-life narrative that we think is applicable to real-world issues.

Chris Lefteri: Thank you very much. Our studio recently had the pleasure of seeing a talk you did in Budapest. Can you give us an overview of this talk as it was very interesting?

Chris Bangle: Sure, some years ago, I was invited by the German government to participate in Potsdam in a particular event that was geared to understanding the coexistence between technology and humanity. The undercurrent thought was: "Will we survive it?" So, I was asked to bring a design point of view into it, and specifically address how design would address issues emerging from this co-existence.

I specifically took to task the idea of the blue-collar worker, let's say the mass of people that the Industrial Revolution took out of the fields and put into factories. And as we've gone through subsequent editions of the Industrial Revolution, technology has developed so that it can and may replace those jobs entirely. The question is, what do these people do? Right?

Chris Lefteri: Yes.

Chris Bangle: My premise was that this type of work turned out to be extremely engaging for a lot of people, it gave them something to do and raised incomes across the world. It provided meaningful employment to people. Now, I'm not saying this is the same kind of meaningful employment as if you were writing software every day or something like that, but for the vast majority of people who really enjoy getting paid to do eight hours of something and then return and have a life, it turns out that factory working is actually quite appreciated. Yet there are countries where we've taken factories away, we've taken the industrial base away from those countries and not replaced it with anything and therefore masses of people don't have anything to do. And the problem is somebody will always give them something to do and that something is not always a good thing.

My thoughts on this were triggered by the Arab Spring Revolution that happened to coincide with the London riots. At the baseline of all the headlines is always "Disaffected Youth Sees No Future". So, I wanted to address this specifically. (I'll come to the materials in a second here.)

And so, I looked at it from the point of view of process. Just finding a piece of paper here. I like to draw on things.

So, the premise is if you take a square and you say, "This is about things which are Predictable. And Precise in regards to process." Obviously, things that are Very Predictable and Very Precise, this is where manufacturing gets taken over by automation the quickest, right? It affects the whole automation base; it spreads from there.

You go down to this corner down here, and you have things which are Very Precise but Unpredictable. This is like surgery. You know, you don't know what you're going to find, but you better not make a mistake.

You get up into a corner here, which is Very Predictable, but Very Imprecise. This is things like agriculture. You know you'll pick the apples on Tuesday, but you don't know where they are.

Finally, you come down to this corner here, which is Unpredictable, and Imprecise. This is generally the service economy. This is healthcare, caretaking, stuff like this, right?

So, basically, I said, if you look at the optimum solution, it would be to put in factories jobs which are Imprecise and Unpredictable because that's the last thing automation would take from people. Right? So, let's shift everything to there. Well, it turns out one of the jobs, which is Very Imprecise and Very Unpredictable, is disassembly for upcycling.

Chris Lefteri: Yes!

Chris Bangle: It's taking shit apart, right? I guess in the days when everything is on Internet of Things and there's a coded number on everything, robots can also take it apart quite easily. I'm not saying that machines can't do everything. I'm just saying, that's probably a good spot to start to keep people engaged.

Well, unfortunately right now, this stuff is farmed out, you know, we ship everything to Africa, we let poor guys work in the field doing this stuff. They're burning insulation off of wires to get at the copper. I mean, it's a horror story! All you have to do is follow Greenpeace on recycling and you get ill by what you're seeing there, right?

So, the trick would be: "How do you get these guys paid well enough to do this?" Because just providing the materials alone isn't going to do it - the raw materials are just substituting something out of the material flow.

The only way to do it is to not go as far to get to the raw materials itself, but stop at the subset. You stop at the parts themselves. That means if I'm going to recycle this [points to coffee maker], I don't grind it into aluminum. Because that wastes all the energy that went into the tooling to make it in the first place. What I do is, I take the parts that are usable, like this, and I use it for it for something else. I upcycle it.

Chris Lefteri: But without destroying the parts?

Chris Bangle: Yes. I don't destroy it if it's still good, but the trick is if we upcycle parts, what are we upcycling them into?

And the theory would be: we upcycle them into a new generation of products that can do something entirely different. So, the whole point behind this is you have to turbocharge the concept of upcycling. I mean, mega-mega-turbocharge it!

And the reason why you're doing it is because you're employing people. That's really the base reason. This is super inefficient. This is a super non-holistic, super inefficient.

Chris Lefteri: You're saying efficient or inefficient?

Chris Bangle: Inefficient!

It's much more efficient to just burn this stuff. It's super inefficient, it's super non-holistic. You know, it doesn't give you pretty things, right. Of course not. You know, if I start combining the bottom of this coffee maker, with this glasses case, it's not going to look like an intentionally designed product? It'll work, but it won't look like it does now, right?

Okay, so let me just finish the story here, and then you'll get where I'm going…

The only reason it works is if you put it in an economic cycle, which makes it work. And fortunately, we have a very good example of that, and that is the zero emission credits that pay for companies like Tesla.

Tesla, for the first years of its existence stayed alive selling credits to those gas guzzler companies, like BMW, Mercedes, etc., who had to pay for the credits or they would be fined tremendously by the government. So, carrots and sticks, right? So, what happened was they paid so much money into the Teslas of the world to make electric vehicles that they not only kept those guys alive, they turned them into a viable alternative for themselves.

What did it cost the government to do that? It costed them nothing, because that's just carrots and sticks. The problem is, governments never know how to distribute money. But with carrots and stick like in the Tesla example, the money goes directly to the guys who give you the credits. So, who needs to get credits? These guys, who make things like cell phones.

I'm going to go out on a limb here and say, probably with companies like that, social responsibility is not the highest thing on their priority list, considering the trillions that they make in revenue, okay? So, having these guys have to buy credits from the operations that are employing people to take stuff apart and have it put back together into other things, maybe it's not a bad idea, right?

Economically, you could get it to balance out from that point of view. The other thing is: how do you actually do this? Like, how do actually put those two things together?

Chris Lefteri: Right, because you're a designer, you're advocating non-design because it's about putting two different parts together.

Chris Bangle: Exactly. Okay, it only works if you use, let's say, AI to identify the parts, which are the closest to being part of it. And then you use the AI to design the interstitial parts, and you use some rapid manufacturing to connect the two. The idea is this type of design philosophy could never exist 50 years ago, because we didn't have a means to put these things together.

Also, if you follow this concept to the next level, the next level is when you designed this coffee maker the first time, you didn't just design it to be a coffee maker. You were already thinking, "What's it going to be next?" This means we need designers who have a mentality to think beyond the immediate product into the next product and get it to work for both. This is a design revolution in many senses. In particular, why would people want to buy something that ugly? Okay, I'll come back to this one.

So, we've proven over centuries that design can make you like anything. 10,000 years of "More is More," and we convinced you in two generations, "Less is More", okay? I mean, design can do anything with your brains.

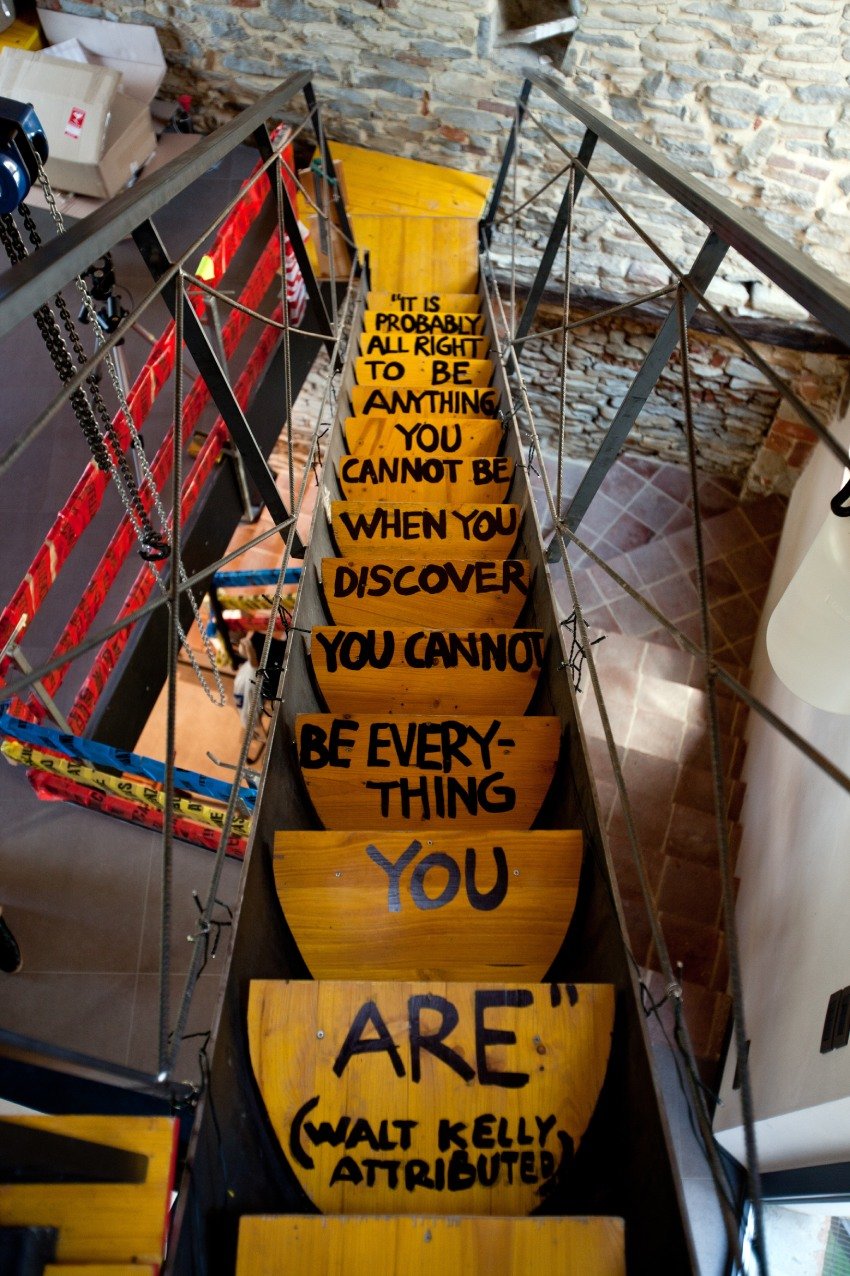

Once it becomes established that, if you don't buy into this new aesthetic, then you belong to the bad guys, once that's established, people will take this, they will accept it into their lives, even if it isn't this holistic, clean, likes-to-be-made-by-machine look.

Chris Lefteri: So, are you advocating a certain kind of, I wouldn't call it "ugly", but a certain reappropriation of how we evaluate what is good and what is bad?

Chris Bangle: Oh, absolutely. Absolutely. Because what you're trying to do at the heart of everything is make humanity viable. We have been convinced by Modernism to like what machines like to make. Hello? We've got to reverse this trend if we want to keep people viable.

Now think of the upside of this in terms of materials. The upside is we're using less raw materials because we're giving multiple lives to what we do make. That's a wonderful thing. We're extending them. So, the upcycling concept is a wonderful starting place, but to make this work, we've got to really engage people. And this starts with a design mentality.

Chris Lefteri: So that role of the designer then changes into somebody who has to find some way to communicate that this has a value, right, because we buy into stories?

Chris Bangle: Exactly, and designers have got to work hand-in-hand with the AI to be able to put this stuff together. So, a designer can't have a too-fixed idea of what they want to have and say. They have to have a vague idea of what it's going to be and then the AI says, "Well, how about if we use this part? I think creativity will take a whole new vision. Instead of creativity being about what is the slickest, prettiest shape I can make? Come on. I mean, every day that goes by, the AI tools are demonstrating they can make slicker, cleaner shapes faster than we can do it. It's got to be, how do I build a story into it?

Chris Lefteri: Right, exactly. So, your vision is to remove the concept of material recycling and say that recycling is about repurposing rather than the embodied energy of having to break something down and then remake it?

Chris Bangle: Yes, I call it 2E, or Second Existence.

Chris Lefteri: And how is that going to work with a car?

Chris Bangle: Well, I mean, you've got a really good challenge on your hands there. In fact, one of the first students who took this on wanted to use parts from, let's say, a washing machine, but he didn't like the washing machine parts as they were. He went back and redid the washing machine so that it would work as a washing machine, but then also as a car fender. And he wound up with a washing machine that was so absolutely surreal. Everybody who saw it said, "That's a cool washing machine. I really want to have that washing machine!" I mean, what can I tell you? You know what I said, otherwise it would be a white box!

Chris Lefteri: I know that the plastics industry is suffering from a lack of skilled workers to operate machines and injection molders and that's something that the industry in Germany in particular is having to address, that no one's going into engineering…

Chris Bangle: There you go. I mean, particularly, one thing is the skilled workers on the line, the other one is the engineers to do it, right? The whole mechatronics industry in Europe, I think, took a shot in the knee when people decided that the only future is software. Now even the software people are turning towards atoms. The physicality of our world, I think, is poised to make a return in terms of importance.

Chris Lefteri: You said that you do training for business leaders. Have any of them given you any thoughts, have you ever discussed this with them?

Chris Bangle: Well, this particular concept I'm very careful not to overly push onto companies because I think it's something the ground for which has to be carefully prepared for before somebody who's got a profit mind can walk on it. If you don't have the carrots and sticks in place, if you don't have the design mentality in place, if you don't have a communication mentality in place, you won't reach the people doing a job where efficiencies and things like this are better than any other alternatives. They're not going to be able to react to this, in my opinion.

That's why my audiences until now have been mostly designers. And luxury pioneers. I think luxury goods is the first that's going to feel this. You never want push to be your major selling point. You want pull. You've got to get it to be the pull. So, it's got to be what the cool people have. It's got to be what's in. It's going to be with the front end. And that's why I'm saying, talking to business leaders about this is kind of distant from where pull happens.

Chris Lefteri: And that's why luxury brands are a good starting point because they create that pull? Aspiration, pleasure?

Chris Bangle: Exactly. And they've already got one foot in art. And if we don't keep this artistic side of ourselves present in this, then we're going to lose another chunk of what it means to be human. And I think the luxury field in general is far more comfortable with the concept of art than let's say product design.

Chris Lefteri: Yes, because when we talk about the aesthetics of these new products, it does remind me of a lot of things that I've been seeing recently, where in the world of plastics and molding, the unfinished, the flow lines become very much part of that honesty, and that move away from perfection. Maybe we're not too far away from having products that are like the toys in Toy Story, the kid next door in Toy Story?

Chris Bangle: Right now, we're working on workshops for creatives in the car industry about what it means to have an emotional connection to a car.

Chris Lefteri: Right.

Chris Bangle: A lot of it has to do with character and character almost always is about a deviation from a norm, which could be found as an imperfection, but it often is something which is a negative. The first page of Harry Potter explains why Harry Potter isn't just a normal boy. He is, except he's got this scar across his forehead and instantly you have a recognizable trait for this character. And as we look at cars that we really love, we've noticed how many of these things embody some imperfection, some less than optimized solution. Yet, that's exactly what makes them memorable, exactly why somehow we hold onto those things. It's less about "We want to build a world of Frankensteins for the sake of building Frankensteins." It's rather, "What is our idea of where character comes from?"

Chris Lefteri: Absolutely!

Chris Bangle: Going back to your question on how we translate this into training for business leaders. Can you imagine a day in the life of a designer in this 2E world? It would be completely different than the one that you and I know. And this is something that I'm trying to get across in management as well. That this idea that management in design is a linear process. Like: "I know where I'm going. And if you deviate from where I tell you to go, I will hammer you back into place onto that."

This is being replaced now by the type of management that says, "Okay, in general, we're headed this way, but we all know by the time we get there, the target's going to change. So, let's see, as you guys interpret this, where your flow takes us, and let's run with what you come up with." And that'll get us to a better target than we could have described at the beginning.

Chris Lefteri: It's a complete mind shift in the education, roles and skills of a designer.

Chris Bangle: Yes. When I brought up the point that we do research here, we're trying to understand this in such a way that it's actually discussable, teachable. We can say "Is this right, wrong, good, bad? How do we measure this?" These are all subjects, which in a true design research phase, we try to answer.

One of the things that interests us very much is "How does this relate to the flow of energy?" Some years ago, Stefan Bartscher, who is the robotics expert at BMW, taught me a lot about how energy use is managed from a system's point of view, so that we can begin to look at things like recycling and upcycling from a different point of view than just the material per se. We begin to look at it differently in a much bigger picture. And that's super complicated, but more and more companies are beginning to like that.

I think in the future, if we want to be a sustainable world, sustainable is not going to be just, "I throw crap away in the best way possible." It's going to be a total cycle, but a total cycle from a much bigger mindset than we have now. Like the total cycle of this [points to coffee pot] is much bigger than we have now. I mean, I keep throwing to you this piece of coffee pot. You have this piece of aluminum, right? Whatever this is, some kind of special fusion metal made for foodstuffs, this stuff has got a hell of a lifetime. And it took real tools to make it that were not simple. Okay. So why should the only future of this be powder?

Chris Lefteri: Yes, absolutely. Before we end, I have one small question which I round up with. It is to ask you, what is your strongest memory of a material from childhood? And the reason that I ask you this question is that it showcases the value that we place on materials is often to do with how they change the way that we feel.

Chris Bangle: Well, I love the question, by the way. It's basically wood because my father sold wood. He was an industrial sales representative for a wood company. Our house was always full of wood. Sawdust, the smell of wood, the plywood, the taste of the screws, you know, because my dad will always say, "You spit on it and I spit on it" and then he'd screw it in. So, there's this whole association of the smell of wood, the cut of wood and the texture, the splinters in my fingers and everything like this.

Chris Lefteri: Fantastic!

K

{Welcome

Create a Core77 Account

Already have an account? Sign In

By creating a Core77 account you confirm that you accept the Terms of Use

K

Reset Password

Please enter your email and we will send an email to reset your password.