The Tactile Media Alliance: Rescuing Touch in a World of Screens

"It's so funny, they're called touch screens, right? And yet, they're not tactile."

When Lindsay Yazzolino was young, she made an origami Christmas tree out of a one-dollar bill. Impressed with how sharp she'd made the topmost point, she urged her mother to examine it for herself. Although her mother assured her that she could see the paper, Yazzolino insisted. Upon touching the point, her mother yelped in pain.

"And I said: 'See, I told you!" Yazzolino recalls. "It's just a different experience."

Blind since birth, Yazzolino didn't expect to make her professional career in tactile graphics. But since graduating from Brown University in 2011 with a degree in cognitive science, and after many subsequent years spent in neuroscience labs, Yazzolino has been leveraging her invaluable expertise to design "hand-catching" experiences that put one of humanity's least-acknowledged senses front and center.

"I remember when I was first studying cognitive science, and the textbooks go: 'vision, vision, vision, vision, vision, vision, vision…aaaaand touch-smell-taste," Yazzolino recalls.

This inequity exists despite how vision exists in a localized structure (the retina) and detects a single kind of sensory info (electromagnetic waves)—whereas touch operates as a diffused sensory network across all of the body's skin and internal organs detecting pressure, temperature, vibration, texture, and more. "Not to say that vision isn't important!" Yazzolino clarifies. "But there's obviously so much missing. People just haven't been studying it."

[Student Competition Winners] Winners of the Tactile Media Alliance Student Design Competiton, Victoria Gamez and Lindsey Yazzolino, standing with TMA Director Abigale Stangl and collaborator Jen Tennison. One person is holding a cane and another holding a bat-themed project box.

Yazzolino is just one of the designers who has as of late joined the ranks of the Tactile Media Alliance. Co-founded in 2019 by industrial design professor Abigail Stangl—who recently came onboard at Georgia Tech—the Alliance hopes to function as both a kind of trade organization, and as a rallying point for touch-minded designers. Georgia Tech, as it turns out, happens to serve as a natural landing place for the Alliance; in addition to the university's long-running braille manufacturing facility (which produced over two million embossed pages in 2024 alone), their Center for Inclusive Design and Innovation also serves as home for the Accessible User Experience (UX) Research Lab and the Assistive Technology Network.

"Accessibility has a long history rooted in ingenuity—people finding creative, often scrappy ways to make the world work for them, using what's on hand," Stangl says. But all the while, "accessibility has been treated as an afterthought, left to individuals to 'MacGyver' solutions. But we're seeing a shift: there's growing recognition that accessibility deserves real investment, not just accommodation. When we prioritize inclusive design from the start, we don't just make things better for disabled people—we make products, services, and spaces better for everyone."

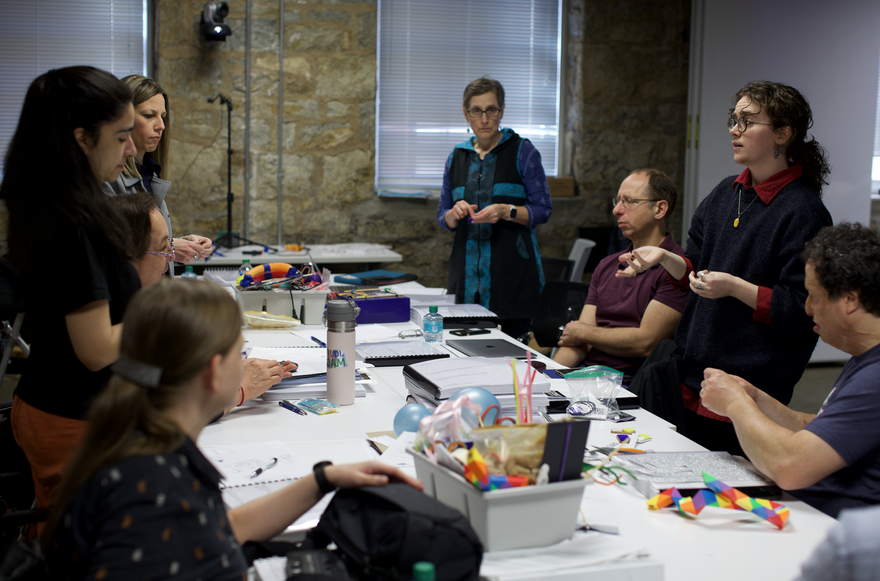

[Student Competition Fidget Group] Group of Tactile Media Alliance Members around a table covered with craft materials, engaged in discussion and hands-on activities. Collin Putnman shares their award-winning Tac-tiles fidget widget project.

[Student Competition Fidget Group] Group of Tactile Media Alliance Members around a table covered with craft materials, engaged in discussion and hands-on activities. Collin Putnman shares their award-winning Tac-tiles fidget widget project.

[Student Competition Fidget] Close-up of hands holding a tactile fidget widget designed by Collin Putnam Tac-tiles. The image shows a small tactile object with a yellow raised shape inside a metal case."

[Student Competition Fidget] Close-up of hands holding a tactile fidget widget designed by Collin Putnam Tac-tiles. The image shows a small tactile object with a yellow raised shape inside a metal case."

TMA's mission has become especially potent during the past few decades, wherein the "touch screen" has essentially become the de facto user interface, from smartphones to electric cars dashboards to ostensibly "smart" kitchen appliances. But this space-age approach has substantial downsides, especially for those who rely on touch to navigate their world; when moving into a new home, for example, Yazzolino's blind friends must often seek out modern appliances whose design haven't yet become totally inaccessible.

"It's so funny," Yazzolino says. "They're called touch screens, right? And yet, they're not tactile."

Although braille still remains one of the most iconic examples, tactile media has made more than a few advances since the script's invention just over two hundred years ago. Raised line drawings, for example, allow for the creation of drawn outlines using carbon-infused ink—typically on specialized microcapsule paper, such as Swell—that raise with the application of heat. The advent of 3D printing, of course, has allowed for the relatively easy production of all sorts of 3D creations (albeit, at a consumer level, out of specialized plastic like PLA). And more recently, enthusiasm has been building for a variety of "Holy Braile" devices, which contain refreshable displays that can provide dynamic and on-demand braille and tactile graphics.

Despite an increasing public interest in "multi-sensory experiences," however, creating high-quality tactile media requires a more nuanced approach than providing a printed or outlined object to be touched. Yazzolino often encounters this first-hand, like when a museum asked her and her team at Touch Graphics - a tactile design company with which Yazzolino has been working for the past decade - to create a touchable replica of a precious Buddhist statue. The statue on its own, however—missing limbs, and covered in faded inscriptions—would not have served as an enjoyable tactile experience. In response, Yazzolino helped create tactile tablets that included the raised inscriptions that would trigger audio of the curator explaining it.

"Visually, you can see everything at once, in the gestalt," Stangl explains. "But tactilely, it's about spatial layout, a progression of learning, building knowledge through hands-on engagement." Compared to the visual experience of taking in a whole scene and then honing in on details, tactile media often operates in the opposite direction. These "tactile skills" are vital, but must be honed with practice (not all blind people read braille, and many become blind or low-vision later in life).

[TMA_HelloWorld] Members of the Tactile Media Alliance standing as a large group holding square textured panels, posing together at the Georgia Tech Workshop on Design for Tactile and Embodied Learning.

[TMA_HelloWorld] Members of the Tactile Media Alliance standing as a large group holding square textured panels, posing together at the Georgia Tech Workshop on Design for Tactile and Embodied Learning.

A modern-day paucity of tactile experience may have arisen from more than a modern industrial aesthetic. "Touch can be stigmatized, so much, because of the sense of intimacy: the degradation, the patina," Stangl says. The recent COVID-19 pandemic—on top of a broader social trend towards individualism and isolation—have likely done little to thwart this inclination. The Tactile Media Alliance hoped to start redressing that imbalance with a three-day "Workshop on Design for Tactile and Embodied Learning" this past February—an exhibit kicked off with a presentation by Stangl's mentor, Ann Cunningham, a Colorado-based artist who Stangl describes as "one of the premier educators who has been advocating for blind-led design education."

"Tactile is just so interdisciplinary," Stangl stresses. "Is it a material question? A media question? An architectural question? A disability studies question? An HCI [Human-Computer Interaction] question? And I think design is really uniquely positioned to bring all of these different perspectives into one place."

As the field evolves, meanwhile, Yazzolino expresses a keen desire that the work of tactile designers be granted the same respect as visual ones. Just how someone isn't presumed to have capacity for visual art by virtue of possessing mere capacity for sight, sighted designers should take care not to presume they have a natural knack for tactile design. By contrast, designers and others in the blind/low-vision community can draw from a wealth of experience and an abundance of personal insight.

"Touch isn't relegated to just accessibility," Yazzolino says. "It's a part of our experience that we could do a much better job at paying attention to. Take the dialogue away from just benefiting people with disabilities, and use our experiences as blind people—who have expertise with tactile products and design—to weigh in, and be part of this conversation."

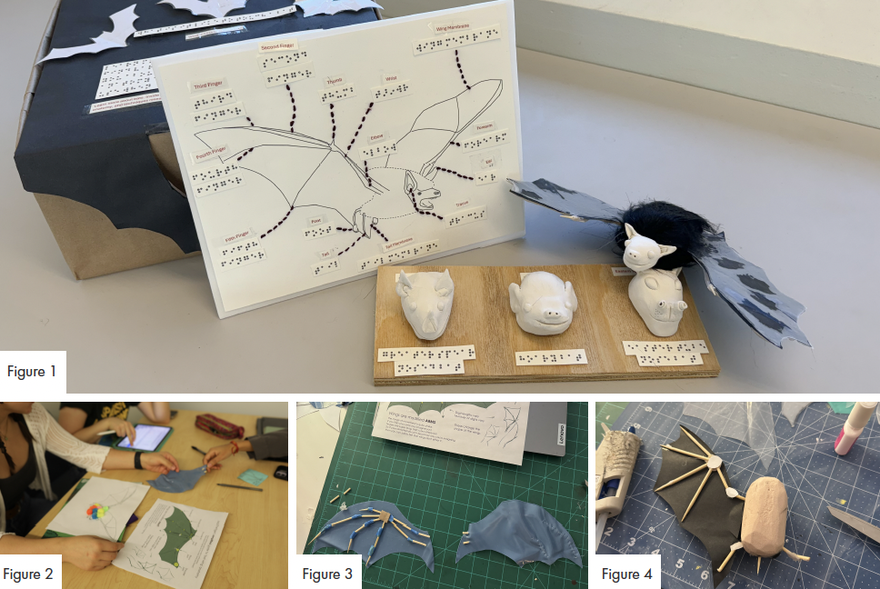

[StudentCompWinner_Bat] Collage of tactile bat anatomy teaching materials, including labeled diagrams with Braille, sculpted bat heads, and wing models in progress.

[StudentCompWinner_Bat] Collage of tactile bat anatomy teaching materials, including labeled diagrams with Braille, sculpted bat heads, and wing models in progress.

During one of Stangl's workshops at Georgia Tech, industrial design students partnered with blind co-designers to develop individual projects. Yazzolino, in collaboration with student Victoria Gamez, designed a tactile learning kit that embodied one of Yazzolino's lifelong passions: bats. Using thin layers of silicone for the wing membranes, skewers for the bone, and sculpted yellow foam wrapped in fur lining for the body, Gamez and Yazzolino's kit allowed users to get close and personal with a friendly facsimile of these echolocating sky puppies. The kit also comes with a raised diagram of the bat's anatomy (with key features labeled in braille), and the whole kit comes packaged in a manner that capitalizes on the tactile experience of unboxing (including a Velcro flap, in the shape of a bat).

"I think it's a more universal and interesting conversation," Yazzolino says. "To think of all these experiences that we want in the world, and to explore those in a tactile way."

-

o1Favorite This

-

QComment

K

{Welcome

Create a Core77 Account

Already have an account? Sign In

By creating a Core77 account you confirm that you accept the Terms of Use

K

Reset Password

Please enter your email and we will send an email to reset your password.